“Politics is merely the desire of individuals and groups to satisfy their basic needs first: food, shelter, clothing, and security for themselves and their loved ones.” – Huey P. Newton

Late last month, the White House convened its first conference on hunger in over 50 years. Politically, the conference allowed the Biden administration to appear proactive on food cost inflation. It also sounded the trumpet of bipartisanism around an issue that’s practically impossible to rail against: hunger. “In every state in this country, no matter what else divides us, if a parent cannot feed a child, there’s nothing else that matters to that parent,” the president said in his address.

On one hand, the conference leveraged $8 billion to expand access to healthy food alongside a pledge to “end hunger and diet-related disease by 2030”; on the other hand, the focus on food industry-driven “solutions” has garnered skepticism. It is highly unlikely that the industry’s worst actors like Tyson Foods (which has been repeatedly fined for employment, antitrust, and environmental violations) and the National Restaurant Association (which lobbies aggressively against minimum wage increases) will do much to advance the cause. “The commitments are a gift from the administration to the marketing departments of some of America’s worst corporations,” said Raj Patel.

In 1969, at the inaugural White House Conference on Hunger, the food industry was similarly called upon to tackle hunger. As Marion Nestle points out, food corporations were asked to educate the public about nutrients, fortify and enrich their products, and reduce the cost of food. Since then, undernourishment of the kind depicted in the 1968 CBS exposé “Hunger in America” has all but vanished, but the prevalence of food-related diseases has skyrocketed. Today, about half of all American adults—117 million people—have one or more preventable chronic diseases largely due to unhealthy food.

Of course, the 1969 hunger conference also led to major expansions of important hunger-related programs like WIC and the National School Lunch Program—initiatives the left has been fighting hard to protect (and expand) in recent years. But those wins didn’t happen in a vacuum…

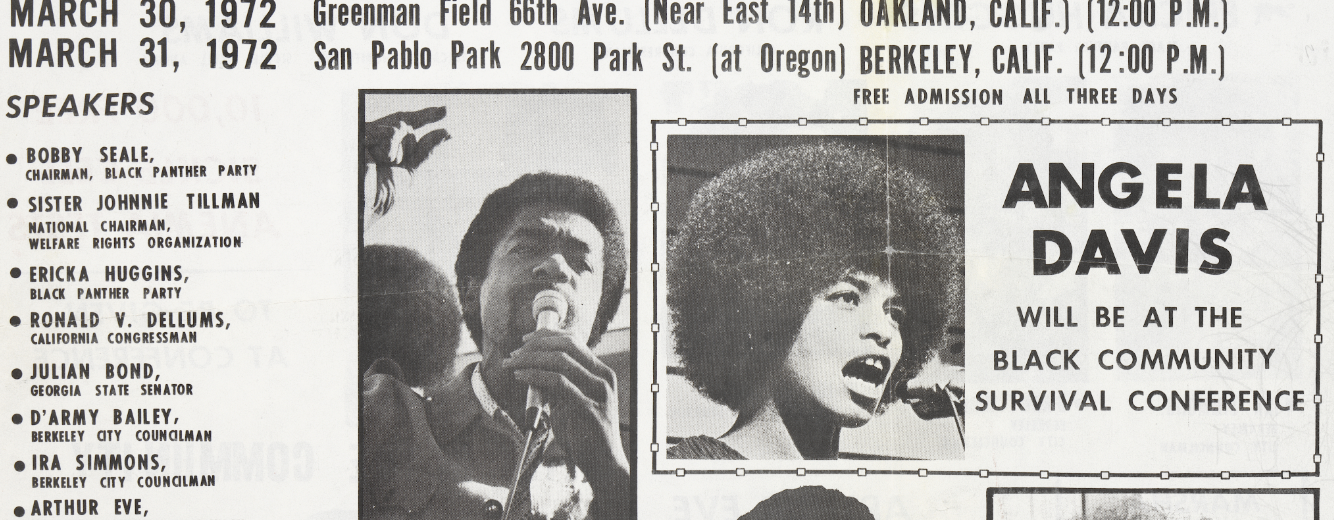

Outside conference doors, teargas hung in the air as protests against the Viet Nam War escalated. The civil rights movement, women’s liberation, student organizing, worker militancy, anti-colonial and anti-authoritarian rebellion, Native activism, Black Power, and other radical movements were in their heyday. Slogans of the Spirit of ‘68 rang out: “All Power to the Imagination!” and “Demand the Impossible!” In early 1969, the Black Panther Party launched its People’s Free Food Program, based on the belief that alleviating hunger was a precondition for Black Liberation. (It’s worth noting that, just as the Black Panthers were pioneering school food and inspiring government programs to come, FBI head J. Edgar Hoover was declaring war on the BPP, threatening to “neutralize it and destroy what it stands for.”)

As we reflect on these twin conferences, 53 years apart, we see that legacy anti-hunger programs are not bequests from a magnanimous government—they are the fruit of intense struggles (struggles brutally repressed, especially when led by communities of color). And so, to our fellow food activists, we pose the questions: What was happening outside those conference doors, then and now, to make policy change both imagine-able and do-able? How are we coming together now to demand the (seemingly) impossible?

In community and solidarity,

Tanya, Christina, Anna, and Tiffani

Read the full issue of the Real Food Scoop

Featured image: Flier promoting the Black Panther Party Free Food Program at the Black Community Survival Conference, March 1972. Credit: Black Panther Party, American, 1966 – 1982 (via Wikimedia Commons)